A conversation between

Natascia Rouchota and Elisabetta Longari

EL Which series of work was Antonio working on when youmet him?

NR He was working on the Quantità; Quantità on canvas in vinyl colour, Quantità on sheets of polyethylene in ink and Quantità on paper in tempera and acrylics.

EL When was this exactly?

NR It was late 1987.

EL On first impression, did you like what he was doing? Orwas it ‘difficult’ for someone who, as I imagine you were, was not a part of the contemporary art world?

NR I had received a classic education in Florence. My knowledge of contemporary art went no further than Lucio Fontana and Piero Manzoni; there was just a blank after that. When people spoke to me of Antonio as the ‘dot painter’. I imagined him to be a loony old man in his fifties doing weird things. Then when I got to his studio and saw these small Quantità of colour on canvas and paper spread around the room, or waiting to be titled and archived, or completely ready, I found myself in a world that was so exciting that I asked him to sell me one of his pieces.

EL Another point that I’m keen to clear up during this conversation, and which your description of colour just now brought to mind, is the rlationship between Scaccabarozzi and Calderara. Do you know anything about it? What relationship was there between these two painters who belonged to two different generations but whose paths of research seemed, at intervals and in some ways, to be really quite close?

NR The first sign of a relationship between Antonio and Calderara was the poster for an exhibition of Antonio Calderara’s collection in Vacciago, stuck on his old white wardrobe. It was a sheet that listed all the names of the artists, and it was the first thing that you noticed upon entering Antonio’s studio. Since everything, for us certainly and especially for Antonio, has a precise raison d’être, there must have been a reason for it being there and not somewhere EL se. The fact that you saw this poster as soon as you entered meant something, it bore witness to a happy, non-conflicting relationship of great respect, where Antonio Scaccabarozzi, and his work, felt completely understood and embraced by an authority on art of the period.

EL It is characteristic of great artists to often have an intuition for and special generosity towards young talents… Lucio Fontana was also able to recognise the value of much work that was sometimes still in the ‘fledgling’ stages, supporting its development by purchasing several pieces. When talking to artists who were around Milan in those years, I often discover that Fontana was the first to purchase from them.

NR Antonio also conveyed a feeling of happiness that derived from this relationship, not just because it was thanks to Calderara that he was introduced into certain circles in Germany, Holland and Belgium, but especially because it happened in a climate of such affectionate serenity.

EL Antonio kept a ledger in which he methodically noted all the technical information, materials, dimensions, dates and news relating to the creation and location of every piece he made; a very useful tool that enabled a mapping of his work in order to build the most precise and complete archive possible. It is a commendable job, which you recently undertook with the support of the P420 Gallery from Bologna. That ledger is certainly crammed with crucial information, are there by chance any more personal observations? Some of Antonio’s texts have been published here and there which are truly illuminating in terms of understanding his work, the mental state and perceptive reality from which his research derives. Are these mixed in with precise ‘book-keeping’ details or are they in other separate notebooks? Are there many notebooks with thoughts and perhaps even drawings, perhaps of a mixed nature?

NR Antonio only wrote about his work when it had already been created and completed, it was as though he wanted to theorise about it with a posteriori. He was not in the habit of making notes beforehand. Not words but small drawings, sketches… so yes, there are various visual notes. The best find from among these materials, words, sketches and notes, are the exhibition designs, which are very interesting. He designed them on a small scale, without the help of a computer obviously, as there were none at the time, with precise colours; he reproduced the whole environment …

EL From what I understand these were not three-dimensional maquettes but two-dimensional designs from many different perspectives, in the style of a ‘true painter, is that correct?

NR Yes, they were all on the surface plane of the paper. And it was only after the work had been created, exhibited and even sold, that he felt the need to write about it, almost as if he had to explain to himself what he had made. Another very curious thing was his notes on the titles. The titles were already strange, hence us collecting some of them in a precious book1, and he often added a comment, which was not however part of the title. For example: “This is not yellow”, or, “Perhaps I should look at this again… but who knows when? As soon as I can”. He talked to himself constantly… in fact he often spoke of himself in the third person, he used to say things like: “This is Antonio’s glass”, I don’t remember ever hearing him say “This is mine”. He also hardly ever used the first-person pronoun; he used to ask “Is there something for Antonio?” Similarly he wrote about his work with a sort of detachment, as though he was talking about somebody EL se… it was really very curious.

Yes, there are lot of information in the ledger, he was very pernickety so he made a note of the names and addresses of all the people who bought his work… that book also showed me that in his last two years he destroyed a lot of his work…

EL Was that because of some sort of dissatisfaction deriving from a form of perfectionism or by accident?

NR As the years passed Antonio became increasingly demanding, so he destroyed anything that didn’t match with what he thought his work should be, without mercy. It really upset me, but there was no way to change his mind, the more time went on, the stricter he became.

EL It seems that there’s a Frenhofer2 hidden deep inside every painter! In fact Antonio’s work, despite appearances, has a very strong instinctual component, indeed as you confirmed, he theorised a posteriori; so his priority was the doing, after which he looked at what he had done and considered which factors had been involved… And yet at the same time this process seems highly systematic, it is as if, through the deconstruction of the language of painting he put fundamental elements to the test, tackling one ‘knot’ at a time, and asking himself every so often: “what is the surface?” or “what is colour ?” and then invariably responding through his work. It was the doing that led him directly on to the next process… Nevertheless I still think it was instinct that drove him, even if it was in a logical direction… What ideas did he have of himself and his painting? Would he have classed himself a ‘conceptual painter’? Analytic? Was he in the habit of labelling himself? Did he have the detachment or courage to do so?

NR No, there was no label that fit.

EL Of course there are never enough categories, but this was more marked in Scaccabarozzi’s case. His work contained components that almost seemed to contradict each other: he would carry out a strict and thorough enquiry into painting that was in some ways minimal, reduced to the mere skeleton of its ABC, but all the materials, from paper to colour, brush strokes and plastic, were viewed with a different kind of involvement, controlled and conscious of the senses, for which the visual dimension was just another component alongside the haptic and more entirely tactile components. The nature of painting, especially in his mature work, was constantly assessed in its variability; it is never abused or substituted by the demonstration of a theorem or theory. It is pure presence…

NR I won’t say that he detested geometry… but he tried to keep his distance; he used to say that it was just a tool and that the surprise hiding around the corner was better for both the spectator and the artist.

EL Antonio’s work hangs in a very equilibrium between the sensuality of the body and the purity of the idea of painting. There is never any emphasis in his work, even in the presence of brush strokes, such presence that they stand out from the support and become autonomous, like in Essenziali. There is presence, but never excess.

If you had to reveal which of Antonio’s series of work you think most interesting and meaningful, which would you choose?

NR I would save the least famous series, his watercolours and in particular those on canvas… there are very few of them and they are almost lyrically beautiful, not mawkish… the colour is so aerial, pure, delicate and dignified, in the sense that it is never too sweet… and then there’s the fact that they’re difficult to make… I only ever learnt painting techniques but I understand how difficult it is to make a watercolour in those dimensions, 70x70 cm or even 70x100 cm, in a single gesture… I honestly don’t know how he did it. For my own personal pleasure I would save these aerial breaths, but if I had to say which of Antonio’s periods of work was very important, I would say Plastiche, the whole series which lasted 15 years in total; initially they were supports for applying colour, then they became the palette…

EL Are there preparatory sketches for Plastiche too? As they are made of pre-existing materials, almost ready-mades of colour, I would be inclined to say no…

NR There are designs for Plastiche, as he cut them and made different, even minimal, interventions on the sheets; there are little drawings that indicate how and what shape to cut the Plastiche.

EL But am I right in saying there are no sketches for Banchise?

NR You’re right, that practice remained a spontaneous choice, like choosing on the palette. Instead of using a brush, he would use scissors to compose. The Plastiche involved a large amount of manual work; it might not be immediately evident, but there was extensive intervention. The result hides the preparatory phase.

EL Do you believe that Antonio had a predilection for any one of his creative phases or did he always just focus his attention and interest on the latest? Sometimes artists are particularly attached to work that has opened doors for them, opened new horizons for the future…

NR He loved exhibiting his most recent work and he didn’t take it well when he was asked to show work that he had made in the Seventies, which he had locked up in a warehouse. That was also the period in which he earned the greatest recognition…

EL And perhaps it was precisely this that annoyed him, because he felt that the request was too obvious and banal…

NR He had the time of his life arranging the Plastiche, which were incredibly difficult to mount, especially in the series he called ‘cancelletti’, which were attached to the wall with a spray, with no wires or nails, no other support. Of course the Velature were more important…

EL Yes because the Velature were also made of traditional painting materials… canvas, colour…

NR Exactly, the more noble materials brought out a different kind of tension in him. It was as though even a speck of dust could threaten their pure, lean, bright and perfect colour tones… But I couldn’t say which he loved the most.

EL The last time I was in Montevecchia he showed me those watercolours on paper accompanied by their bottle of diluted pigment. They were obviously derived from Quantità but showed a different and haptic component that was at times playful and at others conceptual.

NR I think that Quantità was made in the early Eighties for the Angelorasi wine shop in Padua, who had asked for a piece connected to their activity there; so Antonio, who was very attached to his paternal grandfather, ‘the Merate grandfather’, had the idea of paying tribute to him. The memory that lies behind the work was that one sunny day his grandfather, who used to drink wine at the window, turned to his grandson telling him to watch carefully because God would enter his glass through the sun and that as he drank from it he would take in, contain and absorb that divinity within him.

EL Archaic, archetypical and age-old Dionysian roots resurface from this story, the roots of the Christian religion, where wine is a divine vehicle.

NR Antonio recalled having noticed at that very moment that even the tablecloth in front of his grandfather had taken on the colour of the light reflected through the coloured lens, the lens that it had found in the glass which was filled to the brim with wine… Then just like that he had the idea of creating ‘double’ watercolours, or rather, colour spread on the surface of the sheet and colour kept in the bottle, in memory of his grandfather who had given him such a magnificent lesson on the sacred and profane. I think there were perhaps 26 pieces in different colours with the paper and relative bottle. Blues, yellows, reds and so on…3

EL From reading what Antonio has written and talking to you I’ve caught quick glimpses of childhood memories that give us visual impressions of somebody who in terms of his sensibility was already a painter in pectore… That lovely story about his painter uncle and the magical effect of Giallo di Napoli4 that Antonio wrote also shows a precocious painter’s eye.

NR We have photographs that portray him at fifteen or sixteen with brush in hand… he was determined to do this from the very beginning, even as a child he said he would be a painter.

EL But who do you think were his mentors? I mean, when he was in Milan attending the Arti Applicate school at Castello Sforzesco, which artists did he follow closely? Was Fontana among them? Castellani?

NR At the time his hero was Picasso… Antonio came to Milan when he was fifteen to work as a designer/photo-lithographer and stayed for seven years… Antonio was born in 1936 and in 1960 [at 24 years old] he decided to move to Paris principally to find Picasso, to see where he lived and where he created.

His references at that point still did not include the contemporary artists of the Milanese entourage, whom he would pick up later, in fact only when he returned to Italy from Paris [and London and Rotterdam in 1965], having decided to be an artist. One that he loved was Piero Manzoni, his sensibility had moved from cubism and the classical style of Picasso to the Achromes…

EL I thought that the Concetti spaziali by Fontana, monochrome paintings with cuts or stones, might have been the progenitors of his first wEL l-known surfaces, the Fustellati

NR There is no doubt that Piero’s Achromes dEL ighted him and made him dream. Piero’s work has a physicality that must have been particularly congenial to Antonio, the use of michetta [type of bread], wool, cotton… and egg… and then Piero’s operations and those too of Yves Klein. As for Fontana he certainly liked the cuts but also the environments he created. His first love was Picasso, then he grew closer to Piero Manzoni and he loved Mondrian. His direction was much closer to Mondrian than Fontana.

EL Just think, I would have sworn that Mondrian’s commitment to the geometry of orthogonal lines had nothing whatsoever to do with Antonio’s pictorial discourse, which seems of such a ‘heretic abstractionism’ compared to the Dutchman’s style!

NR Initially, in Equilibri statici/dinamici, his starting point was Mondrian, his rigour and line of thought.

EL WEL l exactly, for example, in the Fustellati period, don’t you think he felt close to Castellani?

NR Absolutely, yes, but his distance from Castellani was conceptual in nature. After some years the excessively geometric and repetitive construction/constriction could no longer represent him.

EL I saw Quadrato mobile, 1969, at P420, in Bologna , a kinetic piece that I would never have imagined, are there any others?

NR I can’t reply you. In that period he liked to experiment different languages looking at and testing whatever was around him.

EL Speaking of ‘freed’ dots, you know that other than differences in their personal details, I would liken Antonio’s work to Nigro’s more than anybody EL se? Starting from the basis of a Mondrianesque score organised along orthogonals, he too directed his research towards a new instability…

NR And as a matter of fact Antonio kept a close eye on Nigro, he liked and respected his work a lot, while the art of these introflections and shaped canvases bored him a bit towards the end, but never Nigro.

EL But who were his artist friends?

NR Gianni Colombo above all, we went on some magnificent trips with him in Antonio’s Dyane, which lasted maybe six, seven or eight hours with no breaks. During these trips I would listen to them talking and telling each other many things, between one sandwich and another… There was mutual regard there; with Grazia Varisco too, and then there was his very strange and peculiar relationship with Dadamaino, who I think held Antonio in high regard and he for his part used to say that Dada was the greatest artist of his generation.

EL And during those long car journeys what did Gianni and Antonio talk about? How did they interact?

NR I was present for conversations which were often technical in nature, about certain materials and the way they responded, drawing techniques, forms…

EL They exchanged views and information…

NR And intentions too, “I’d like to do this…” , “That time I wanted to do such and such but I didn’t manage it… I could have but…” In the early Nineties Gianni and Antonio were often invited to exhibit together in various museums in Germany and so often they went… Sometimes it even got a bit ‘Amarcord’…, “Do you remember when we went there and did…”. Another artist that Antonio loved was Rodolfo Aricò, of whom he spoke with great admiration and he also really admired Raimund Girke… Anyway, you know, Antonio worked a lot and had little to do with the art world, we would travel, dance tango, he would ride his motorbike…

EL To return to art and his love for light and the air that circulates through its colours, I think that in terms of the historical masters we can’t leave Tiepolo, Vermeer and Watteau out…

NR I’d say Vermeer more than the others, because his light, which lit up his interiors, was very measured, intimate yet strong. Antonio loved anything that wasn’t striking, he often quoted Micheal Seuphor’s book Le Style et le Cri.5 It was no chance that he preferred Piero della Francesca to RaphaEL , Leonardo to Michelangelo, Cèzanne to Van Gogh, Mondrian to Burri or Rothko to Pollock. His way of ‘exploding’ was with style, with tact, not with a desperate cry.

EL An almost minimal certainly essential, although effusive and emotional, line emerges from this list, of colour, introduced and reasserted by almost all those you have named, a line confirmed by Antonio’s connection with Calderara.

E. L.

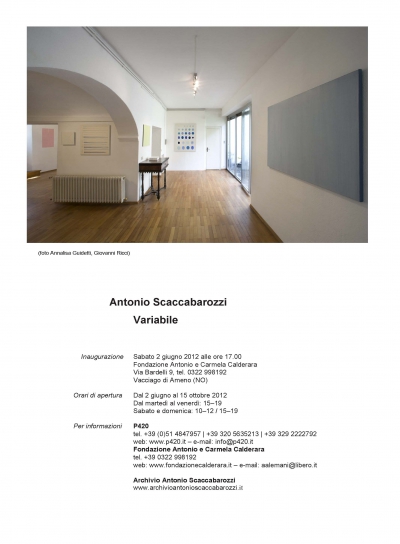

Il catalogo, edito per l’occasione, presenta diversi materiali: il testo introduttivo della curatrice Elisabetta Longari, La conversazione con Natascia Rouchota, compagna del pittore e responsabile dell’Archivio omonimo, sopra riportata, gli apparati di rito e le riproduzioni di un’ampia selezione di opere, tra cui tutte quelle presenti in mostra, anche ambientate nello spazio della Fondazione Calderara.

Per il catalogo della mostra rivolgersi alla galleria P420 Arte contemporanea, P.za dei Martiri 5/2, Bologna.